Artist statement

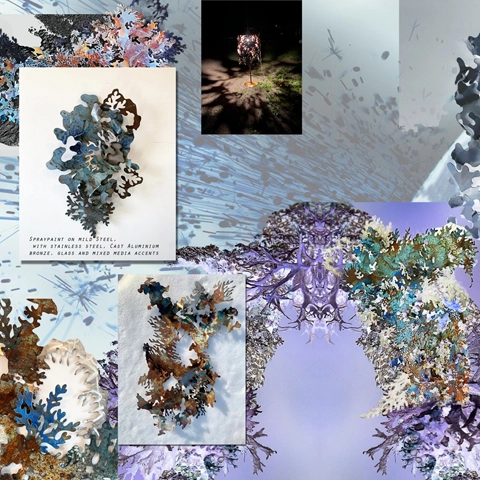

This body of work interrogates the complex entanglement between industrial and environmental processes through organic forms, exploring steel as base for evoking the delicate yet persistent structures of lichen, coral, and other biomorphic growths. By employing hand-carved plasma cutting and layered automotive pigments, I embrace the tension between industrial decay and natural resilience, revealing how material processes inscribe themselves into both environmental and social narratives.

The sculptures take inspiration from lichen, a composite organism that thrives in liminal space—a symbiotic entanglement of fungi and algae that exists between worlds, neither fully plant nor fungus but the relationship between the two. As a bio-indicator, lichen’s capacity to extract nutrients from the air makes it acutely responsive to environmental change, mapping the shifts of industrial pollution and climate change across its fragile structures. My interest in lichen began during an Arctic residency in eastern Iceland, where I observed its capacity to colonize barren landscapes, covering rusting steel elements of the abandoned fish factory we were working out of, quietly asserting itself against inhospitable conditions. Informed by this resilience, my sculptures mimic lichen’s intricate growth patterns while alluding to the broader human and geological forces that shape planetary processes. These forms simultaneously recall the shifting topographies of tectonic plates and the minute fractal structures found in microcellular life, underscoring the collapse of distinctions between the macro and micro in an era of climate crisis.

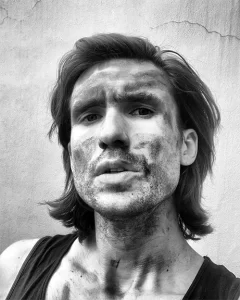

By privileging hand-carving over CNC automation, my work resists the sterility of digital precision, foregrounding the haptic labor and improvisational potential inherent in manual Craft processes. This decision speaks to the erosion of the proletariat in the 21st century and reflects my ongoing engagement with the precarity of industrial craftsmanship and labour. Plasma cutting by hand invites a performative element to the creation process, recalling the intuitive gestures of drawing while invoking the corporeal memory embedded in traditional carving practices, instead of wood and stone, I carve the unnatural resources of the past sourced from the scrapyard instead of the marble quarry. This tactile approach positions the sculptures as artifacts of embodied labor, simultaneously fragile and resilient.

The bodily resonance of these sculptures is central to their material and conceptual grounding. Steel, as a material, holds a deep connection to the body — not only as tools of industrial labor, but on a chemical level as well. Both rust and blood share a vital common element: iron oxide, the same molecule that spreads out across the Rust Belt delivers crucial oxygen from the heart to the extremities. This parallel suggests a visceral link between the slow corrosion of steel and the inevitable processes of aging, injury, and mortality of the industrial worker. The hand-carved plasma cutting process reinforces this embodied connection — a practice of guided violence where the body’s movements are translated into jagged cuts and molten edges. The labor-intensive process recalls the theories of Richard Sennett, who argues that Craft is fundamentally tied to the body’s capacity for skilled repetition and embodied knowledge. By embracing hand-carving over CNC precision, the sculptures bear the traces of physical strain and improvisation — gestures that echo the fraught relationship between human labor and industrial production. In this sense, the work becomes an index of the body’s presence, with the patterns of lichen-like growth inscribed through sweat, control, and exertion.

The surfaces of these sculptures, layered with automotive pigments, evoke both the mottled hues of lichen and the corroded patinas of post-industrial ruin. The steel’s inevitable oxidization mirrors the decay of manufacturing and social infrastructures in former industrial centers. These material choices speak to what theorist Jane Bennett describes as “vibrant matter”—a recognition of materials as active participants in social and ecological systems. Here, the rusting steel becomes an index of environmental flux, a visual register of both industrial degradation and nature’s adaptive strategies. The sculptures oscillate between states of growth and collapse, underscoring the fragile equilibrium between human intervention and ecological persistence.

Accompanying the metal forms are sculptural elements cast in Styrofoam—synthetic artifacts that stand in stark contrast to the organic deterioration of the steel. While the steel decays, these plastic remnants persist as unsettling markers of anthropogenic permanence. Their presence evokes Timothy Morton’s concept of “hyperobjects”—massive, distributed entities like climate change or microplastic pollution that transcend spatial and temporal scales. These synthetic fragments become speculative monuments to a future defined by the detritus of contemporary industry.

Sound is a critical element in this body of work. Through the integration of contact microphones, synthesizers, and a modified metal detector and theremin, the sculptures are transformed into resonant instruments. Subtle movements and shifts alter the sonic landscape through the vibrations of the material that echo seismic activity, electromagnetic interference, or the aesthetic experience of the crunch of lichen beneath the foot. These auditory layers evoke the unseen forces that shape both natural and industrial environments, reinforcing the idea that materiality is never static but in constant negotiation with its surroundings.

By combining materials that corrode with those that endure, this body of work reflects on humanity’s entangled relationship with environmental systems and industrial debris. The sculptures suggest a post-human landscape—one in which lichen quietly reclaims forgotten infrastructures and the remnants of industry become fertile ground for emergent ecologies. In this way, the work invites reflection on the delicate interplay between decay, regeneration, and our own precarious position within these unfolding narratives.

Relation to Bancroft/ Site Specificity

Bancroft’s identity as the Mineral Capital of Canada presents a compelling context for this body of work. The region’s geological richness — defined by veins of iron ore, quartz, and feldspar — echoes the material language embedded in these sculptures. Minerals, like lichen, record environmental histories, acting as silent witnesses to deep geological time. Just as lichen absorbs airborne pollutants, minerals bear the scars of tectonic pressure, heat, and chemical shifts — a slow archive of the earth’s transformations. In this sense, both lichen and minerals are sites of memory, accumulating traces of environmental change across vastly different scales of time.

The steel sculptures, with their rusted surfaces and automotive pigments, draw an unexpected parallel to Bancroft’s mineral wealth. Rust — a form of iron oxide — mirrors the earthy reds and ochres found in iron-rich stone, reinforcing the notion that these pieces are geological in nature, mimicking not only lichen but also the mineral processes unfolding beneath our feet. By positioning steel — an industrial material forged from mined iron — alongside forms inspired by lichen, the work reflects the uneasy intersection of extraction, industry, and ecology.

Moreover, Bancroft’s mining legacy offers another layer of resonance with the sculptures’ engagement with labor. Mining is an industry that, like steelwork, is deeply entwined with the body — reliant on physical exertion, endurance, and risk. The plasma-cutting process, with its sparks, heat, and molten edges, recalls this relationship — a bodily negotiation with resistant material. In a place like Bancroft, where the land has been marked by both geological processes and human excavation, these sculptures can be read as a meditation on the tension between extraction and regeneration, decline and renewal.

In this context, the installation offers a dialogue with Bancroft’s landscape — a reflection on the region’s mineral wealth, its industrial past, and the fragile ecologies that persist in its wake.

About the artist

Garrett is a professional sculptor from Douro, east of Peterborough Ontario. They initially studied welding and fabrication at Sir Sanford Fleming College, before receiving their BFA from NSCAD University in Halifax, and studied abroad at the Gerrit Rietveld Acadamie in Amsterdam. Garrett describes themself as “a carver of unnatural materials, instead of wood and stone, I intricately carve discarded tools, car parts and other salvaged industrial steel objects collected from the forests and scrapyards of rural Ontario”. The work is typically carved with a handheld plasma cutter, a welding torch used for melting and cutting steel that would typically be integrated into a computer controlled table, by using the torch freehand Garrett expands the flexibility and possibilities of the tool.