Artist statement

Of the knowledge and wisdom that defines you, do you include what you consider second nature? Where is that deep place of knowing? In your mind? Your body? Both?

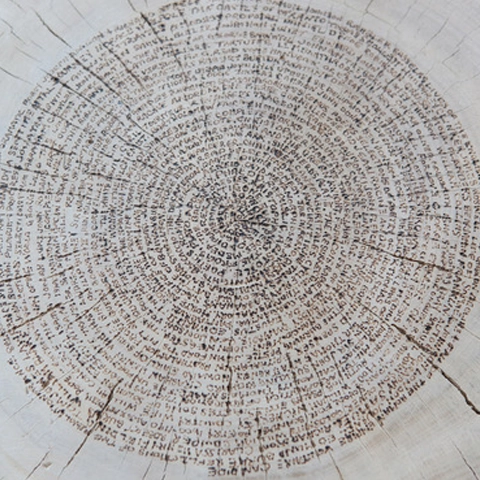

Much of my work examines the nature of memory and how we know things. I’m intrigued by the roles that symbol and language play in coding memory and the ways in which recollections are organized into what we understand as history. My interest in memory stems in part from my family history (Alzheimer’s runs through my father’s line) and from insights gained in the years after a tumour was removed from a learning and memory centre in my brain in my late twenties.

The inspiration for this project was a vintage how-to paddle manual and several documents I had stored together decades ago. The documents included a list of must-read books, from antiquity to the late 1900s, a paper detailing the skills required to achieve canoeing excellence, and two essays — one on how to write an essay, and the other on how to write a resume.

On finding the collection I recalled my state of mind from when I assembled it. I wanted to be a better writer, more learned and prepared for adulthood. And I wanted to be a master paddler—not necessarily in that order. It was my final year of university. What next?

The energy I sensed coming from the collection drew me in. There was a delightful earnestness to it, but also trepidation. Plus, the idea of relying on a manual to improve skills not easily learned from a book baffled me, especially since I already knew how to paddle, and well. I began to wonder about the type of knowledge the collection didn’t represent.

Where were intuition and trust? Where was the mind of the body?

Ironically my canoeing manual provided key insights. On closer scrutiny of The Canoe and You I noticed I was less interested in what the book was trying to teach and increasingly drawn to the other wisdom I sensed running through instructive text. I was struck by how many passages could be understood as universal truths if removed from their context. How for instance, “paddling in rough weather know-how” can apply to any hardship:

“In a very heavy sea, assuming you get caught out in one, strive constantly to keep the canoe from turning away from a true line.” — R.H. Perry, The Canoe and You, 1946

I found many truths in that one volume, in fact once I started seeing them, I couldn’t stop. I studied other manuals and noticed the truths seemed easier to tease out when they pertained to something I was already good at. Navigating rough water in a canoe, for example, is second nature to me. I understand Perry’s advice, but the mind of my body—the feel of my paddle and canoe, the wind and water—is what I trust.

These observations inspired me to ask others to assist in my research during an artist residency I called How to do Anything. My methodology was to host salons where I invited participants to mine my growing archive of manuals for their own truths. Could we expose the tension between what we know in the mind and what we know in the in the body? What would that look like?

Solemn, quirky, ironic? Since my earliest explorations, I have been translating these ideas and findings into text-based sculptures and mixed-media encaustics. I like to think they and the collective act of noticing that went into their making offer hope.

knowing; being is a work in progress.

About the artist

Wendy Trusler is an interdisciplinary visual artist from Peterborough who creates site-responsive installations incorporating drawing, painting, writing/text, sculpture, performance, and film. She is also a baker, cook, published author and onetime dancer — callings that continue to inform and are integrated into her practice.

Much of Wendy’s work examines the nature of memory and ways in which recollections are organized into history. Shaped by the experience of having lived in seclusion in wild places, ideas around ecology, continuity and regeneration play out in her material choices and physicality of her work.